The larger the organization or project, the more complex and involved the work. A small team of three might be able frequently enough to coordinate, but a group of 12, a stream of 100, or an organization of 1000 can scarcely achieve that. Instead, technical leaders define what to accomplish and how to achieve those goals and document it in a way everyone can easily use as a reference.

Two indicators of a productive and satisfied engineering team are when every team member understands the team’s technical direction and how the work they’re currently doing contributes to that direction. As senior technical leaders, it is part of our role to establish that direction and a plan for how to get there.

A few words need to be defined to discuss these concepts in detail. Vision, strategy, goals, and mission are often used in overlapping ways. Here’s how the terms will be used:

- Vision – a long-term view with high-level goals. It briefly describes the current state and projects the future state; it can be aspirational (i.e., what to accomplish).

- Strategy – how teams, systems, and processes work individually and collectively to implement and achieve the vision (i.e., how to achieve it).

These concepts take written form but should not be set in stone. It should not require continuous rewrites but a strategy must be adaptable to changes. A six-to-nine-month timescale is ideal for it to stay relevant. It should be reviewed and updated with key learnings discovered along the way.

Set the Vision

A core responsibility of the architect (or team lead) is to ensure a shared understanding of the team’s direction. A clear technical vision is essential to ensure that the entire team pulls in the same direction. It serves as the team’s “North Star” to motivate and guide the group as it grows. The vision zooms out to give perspective on why the team or organization exists. Rather than articulating the specifics of team operations, the vision describes how the team or organization seeks to impact and improve the world around it.

Think of the technical vision as a tool to analyze, align, and execute long-term technical goals in teams or organizations. Technical goals are aligned with stakeholders and then communicated across the organization. It’s a perpetual cycle: goals are brought into execution plans, the outcome is measured and evaluated, and then learnings are collected and used to improve current and future technical visions.

Technical visions can change over time. This reflects changing business requirements, best practices, and the technology landscape. Changes may also reflect expressing the intention behind the vision more effectively. While technical visions need not be detailed or specific, the intent must be unambiguous. It is the architects’ responsibility to communicate the idea effectively.

Analysis and alignment

Each technical vision cycle begins with evaluating the current reality. Take time to understand the historical context behind the decisions that created this reality. These decisions were made based on the facts at that time; there’s a lot to learn from this. To position ourselves for the future, we should analyze past decisions and how those served the stakeholders and requirements. Once the future direction is decided, work to identify the current and future state gaps.

The technical vision should have the backing of stakeholders and the team (managers and engineers). Not everyone can be involved as the team scales – use discretion to determine who to include in this process. Key players should contribute; this will aid in the buy-in process because they have a personal investment in the undertaking and, therefore, a vested interest in its success. Invest in the art of persuasion.

Gain credibility by involving stakeholders in the process (i.e., bring them on the journey with you) and incorporate their ideas into the vision (and, later, strategy). Don’t forget that non-business stakeholders (e.g., documentation writers) have valuable thoughts too. A wise architect may note all feedback but prioritize stakeholder requests that echo their thoughts while balancing the business context. Everyone should be aligned on how delivering on goals achieves the desired outcomes.

Characteristics of a vision statement

There is no one-size-fits-all for crafting a technical vision – each is unique to the team or organization and the current business context. Despite no specific template, there are a few common characteristics of well-written visions:

- Keep it brief – a vision statement should be easy to read and follow; cut out the fluff and keep just the essentials.

- Keep it simple – stakeholders and teams should understand the vision. Avoid “industry-speak” where possible; plain language is always more powerful than jargon or buzzwords.

- Avoid ambiguity – focus on a clear objective; a vision does not need to be concrete in the manner that a mission does but should avoid possible misinterpretations.

- Be future-looking – think long-term (i.e., 3-5 years); a vision statement is set in the future when its objectives have been met.

- Be challenging – describe the most ambitious and aspirational objective to convey a sense of passion for the ideal future; it should be challenging enough to motivate the team to work towards achieving the goal.

- Be feasible – others have to buy into the vision for its goals to be achieved; the vision should resonate with the team or organization and inspire them to move forward. The goal shouldn’t be so far out of reach that it feels impossible.

Remember that a picture is worth a thousand words. A visual image can add a lot of clarity to vision and strategy documents around key pillars/components and their relationship to one another.

Define a Strategy

If a vision tells you where you want to go, then a strategy is the path. The starting point for a good strategy is knowing where you are today. But it is also essential to understand how you got there; learning the culture and context will help shape the way forward. A strategy is an approach to a problem that recommends a specific course of action that address the problem’s constraints. The strategy’s what, how, and why must align with the technical vision. Writing a strategy leads the driver through a systematic analysis that can help work through challenges.

To do that, you need to define the current state, capabilities, an understanding of strengths and weaknesses, and what external factors could positively or negatively affect the strategy. Any consideration of a technical solution should be followed by a consideration of the people who can implement the solution (not just in terms of the amount of effort, but also what is needed in terms of roles, responsibilities, and skill sets). In addition to technical solutions, consider whether the necessary processes are in place.

Values and principles

Engineering values and architectural principles are the cultural cornerstones of an organization’s strategy. They are the foundation that feeds into and guides the process to ensure it’s shaped in a way that reflects the overall mission. Together, engineering values and architectural principles articulate the desired approach but allow teams to maintain autonomy in a coordinated and aligned manner.

Engineering values cover the engineering organization’s culture, including what is valued and how to work together. Values are common beliefs defined that act as guardrails to align the value systems across teams. An example of this is “Move Quickly and Iterate.”

Architectural principles lay out a shared technical philosophy to guide decision-making. Principles are intended to empower engineers to make decisions and provide strong guidance for making those decisions in a way that is coherent with the overall strategy. The principles offer dimensions to weigh options when making a technical decision.

Forge the path forward

People are usually comfortable with difficult decisions in the abstract but may struggle to translate them into specific actions or implementation steps. A good strategy avoids choosing particular technologies. Instead, it focuses on defining components and key concepts and identifying functional and non-functional requirements. A strategy should define:

- The current state as a narrative aided by high-level diagrams and quantitative and qualitative analysis.

- The future state with commentary about what we are trying to achieve, aided by high-level diagrams.

- A transition plan to achieve the future state includes specific next steps or decisions.

Ensure the document walks through key business use cases and demonstrates how the components interact. It’s important to define the core systems and components of the architecture and their responsibilities. A great way to solidify an understanding of responsibilities is to focus on boundaries when walking through use cases by declaring for which each component is responsible (or not responsible).

Execute the Plan

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory, tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.” (Sun Tsu)

The execution phase of the technical strategy involves planning and prioritization, and delivery. At this point, the actions listed in the strategy are translated into a multi-quarter roadmap that maps to goals.

The first steps are to size and sequence efforts. Where possible, use milestones to indicate some value delivered. Make sure the planning process is open and collaborative; roadmaps help a team navigate their role in delivering the outcomes described. Collaboration, by default, helps to ensure the team is aligned with the vision and strategy.

The delivery path can be long and arduous, sometimes successful, often oblique, and unfortunately riddled with FUD. Secure early wins to assuage fears and uncertainty. Focus on impact and return on investment when selecting which work to prioritize and identify possible partnerships with other teams that can help drive execution.

Short-term, incremental milestones

Long-term visions outline a system(s) or project(s) that may take several years to complete. Over this period, we will learn new information that needs to be incorporated into the plan and help define the subsequent actions. Businesses shift quickly, and you need to be able to adapt to that change. This involves ensuring the delivery plan is incremental and collects rapid feedback. When coming up with short-term, incremental plans:

- Don’t try to define every milestone through to the end delivery. The vision is directional and will likely evolve and shift as we learn more with each milestone. Instead,

- Look for milestones achievable within a shorter window (e.g., 3-6 months, or shorter depending on the size and scope of the project). Each milestone should deliver value, such as a business or technical win. Know why it is a milestone.

- The long-term vision is a guidepost. Milestones should align with the end goal but allow room to veer slightly off-track if there is a good reason. Always be wary of scope creep.

Start with low-effort, high-value work to deliver quick wins, and build momentum and confidence. As a process is made, something built or learned in the previous milestone can sometimes make another milestone more achievable – compounding momentum.

Market the plan

Never present a strategy the team hasn’t heard before. Having the right people in the room at the conception stage is essential to get everyone on board. Think about who will provide core insights from both the business perspective and the technology side.

Craft the narrative to suit the audience. Highlight the reasoning behind the strategy and how it impacts them. You might need additional headcount or commitments from other parts of the organization, so you will need support from leadership or other teams. Be prepared to negotiate, and incorporate this back into the execution plan.

Seek a sponsor to endorse and advocate for the vision and strategy. Ideally, this person is a leader who is in good standing, will go to bat when needed, and has a vested interest in the successful delivery. This type of endorsement can go a long way to substantiate the value of the work.

Measure the Outcomes

“However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.” (Winston Churchill)

What does success look like for your team and its stakeholders? Were the principles adhered to? How do you know when the vision has become a reality and the mission is achieved?

A technical vision and strategy outline goals to be achieved over a time boundary. These are expressed as objectives. The outcome translates into key results. OKRs and KPIs should be specific and outcome-focused, with clear and relevant markers to measure progress.

Consider what data should be collected, why, and how. The action plan developed as part of the strategy should list the metrics to be tracked. When progress is small and incremental, data is critical in demonstrating whether the strategy is working or not. Metrics should be clearly tied back to the strategic objectives.

Be open to exploring options, and be intentional about tradeoffs. Use rapid prototyping and iteration to add incremental value and discover unknown unknowns at each stage. The goal is to gain enough data and insights to empower decision-making, (re)evaluate the following steps, and de-risk throughout the process.

Useful Frameworks

This section provides a few frameworks you can adapt for writing vision and strategy documents.

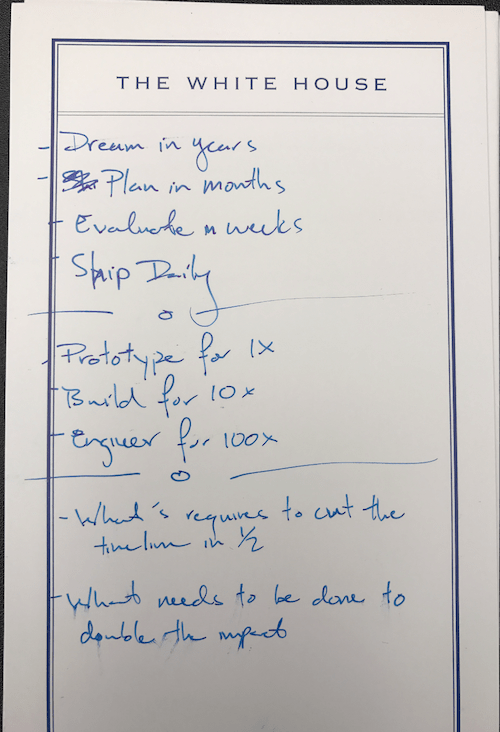

Patil’s Project Principles

DJ Patil was the first US Chief Data Scientist and part of the Obama administration. During this time, he created a simple checklist emphasizing the need to iterate fast, plan big, experiment, and then engineer to scale, focus on the highest value, and cut waste.

Patil’s checklist has much in common with Lean Thinking and the Pareto Principle and can act as a high-level guide for developing a vision and strategy.

BAMCIS

BAMCIS is probably the most ubiquitous acronym in the US Marine Corps. It is a tool to assist leaders in making tactically sound decisions, formulating plans, communicating them, and turning those plans into action. The six steps are:

- Begin the planning – determine what needs to get done and what information is required. During this time, you may develop questions about the vision or project for which you do not have the answer. This creates the plan for the plan.

- Arrange for reconnaissance – develop a list of research objectives and methods for gathering the information needed.

- Make reconnaissance – execute the research and validate hypotheses. Compile the information gathered to finalize the plan.

- Complete the planning – revisit the initial plan, armed now with the answers to earlier questions. Build an operable plan to execute the vision.

- Issues the order – effectively communicate the vision and align all contributors around the same objective.

- Supervise – ensure that the right outcomes are achieved.

There is a common saying in the Marine Corps that no plan survives first contact; BAMCIS is a highly adaptable framework that can aid decision-making and planning.

Good Strategy / Bad Strategy

Good Strategy / Bad Strategy by Richard P. Rumelt takes a fuzzy concept and makes it clear. He explains what it takes to develop a strategy, the elements of a good strategy, and what makes some strategies bad. The book describes three aspects of a good strategy:

- Diagnosis – defines the challenge and describes what is holding you back from reaching your goals.

- Guiding policy – the approach chosen to overcome the obstacles identified in the diagnosis.

- Coherent action – describes how to carry out the policy.

Rumelt says that identifying and solving problems is the core of strategy. The book is worth the read, especially for architects (there is a lot of overlap between strategy and design work).

Conclusion

Once the strategy is written, it should not go stale. Until the vision and strategy are actualized, the documents should be revisited about every six months and updated with any learnings or changes. An effective technical strategy provides the map that sets the course toward the north star vision.