Our team at Rubrik uses Terraform extensively to manage our infrastructure as code. This means that our infrastructure configurations are version controlled and resources are provisioned in an automated fashion through CI/CD workflows. Because it’s a customer-zero environment, we’re constantly evaluating new tools to find better ways to manage and scale the environment. This led us to trying out Terraform Cloud.

Easy collaboration is the name of the game with Terraform Cloud. It offers team-oriented remote execution and is consumed as a SaaS platform. In this post, I’ll cover remote state management, cost estimation, and collaboration with Terraform Cloud.

Remote State Management

State files capture the existing state of provisioned infrastructure for a specific workspace. State files are stored on the local machine by default. This becomes unwieldy when the rest of the team is involved.

Remote state management is a design consideration with which we’ve extensively experimented. My colleague, Chris Wahl, has written about using Amazon S3 to store state, which is how we have historically managed state. This resembles the following:

terraform {

backend "s3" {

bucket = "technicloud-bucket-tfstate"

key = "dev/terraform.tfstate"

region = "us-east-1"

}

}Using Terraform Cloud to manage remote state resembles the following:

terraform {

backend "remote" {

hostname = "app.terraform.io"

organization = "technicloud"

workspaces {

name = "scaling-compute"

}

}

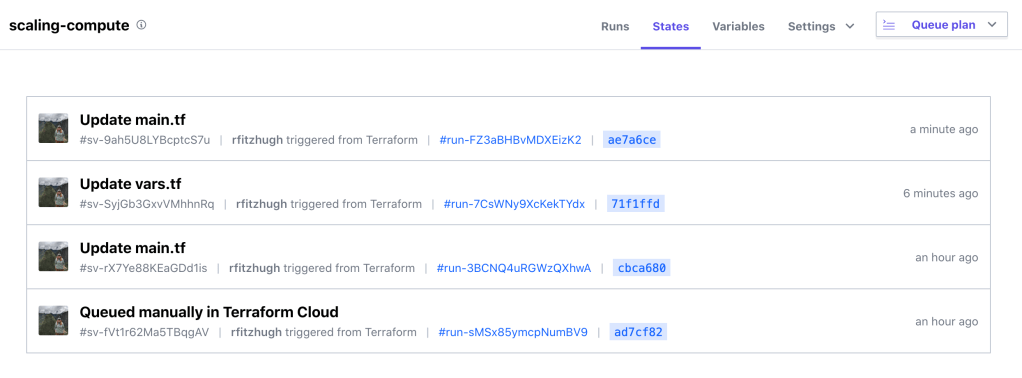

}With Terraform Cloud, the state file is abstracted from the user; it exists but is secured and managed by the platform. This allows for granular access control, versioning, and backup so that I’m able review previous points in time. While Amazon S3 provides these same features, it requires quite a bit more effort to do so. For example, remote state management with Terraform Cloud provides integrated locking, eliminating the need to spin up a DynamoDB table.

Terraform Cloud enables teams to easily collaborate asynchronously by using the platform as remote state file storage.

Cost Estimation

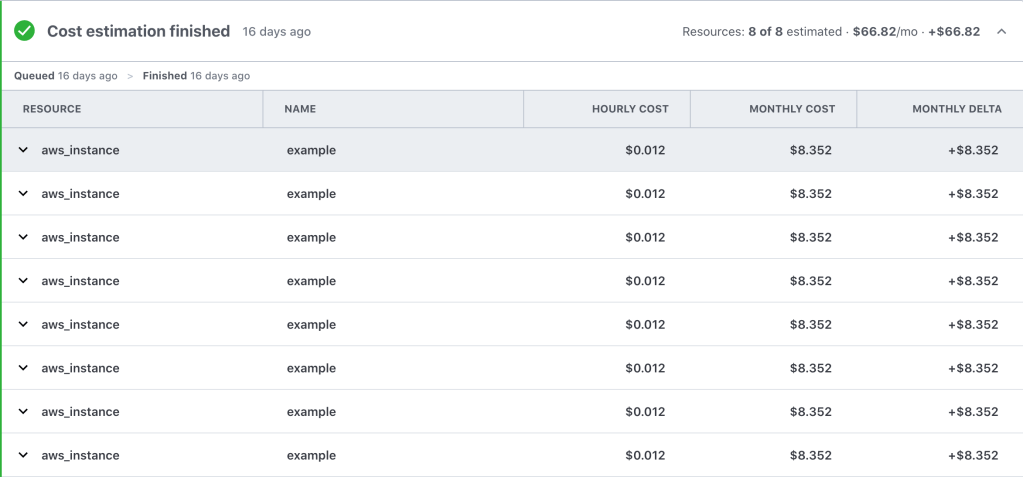

A very cool feature that stood out was the cost estimation, which displayed an approximate monthly cost with each workflow run. This is particularly beneficial to me because we use Terraform to deploy resources across all three major cloud service providers. Holistic billing management across multiple clouds has long plagued me:

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jsFor 59 days I have been focused on migrating and consolidating billing for AWS, GCP, and Azure.

— Rebecca Fitzhugh (@RebeccaFitzhugh) August 23, 2019

I apologize for whatever I did to deserve this. pic.twitter.com/s0mRdruDIa

This standard interface provides a valuable way for our team to analyze, report on, and visualize cloud spend across cloud providers.

While this alone does not give a complete picture of our monthly bill, it certainly helps us be mindful of cost when testing and building demos. We are regularly building demos to showcase our product’s cloud functionality; this process consists of design time spent architecting a solution and then usually a lot of prototyping to get the demo perfect. The prototyping phase consists of deploying and destroying resources numerous times, which can quickly rack up a big bill when not paying attention to cost.

However, the Terraform Cloud Cost Estimation API provides a lot of granular data that can be pulled into our central billing dashboard. This helps us be mindful of monthly costs to operate our cloud environment. Using this data, we made the decision to use demo leases of 4 hours to help minimize costs for demo; after 4 hours, the resources are stopped. This helps us keep central IT off our backs 🙂

Team Collaboration

Terraform Cloud offers a number of collaboration features to help teams easily work together. Our team prioritizes making our code as reusable as possible; we regularly write modules that fit our design specifications and use cases. The Private Module Registry allows us to easily share the different use case modules that we’ve built.

There’s also multi-tenancy with the ability to create and manage multiple teams and organizations and enforcing Role Based Access Control (RBAC) across the different workspaces. Moreover, you can manage Terraform Cloud configurations using Terraform.

Here’s an example of using the Terraform Cloud provider to create an organization, workspace, team, and permissions:

# Create the Terraform Cloud Organization

resource "tfe_organization" "technicloud" {

name = "technicloud"

email = "rebecca@technicloud.com"

}

# Create the Technicloud Workspace

resource "tfe_workspace" "technicloud-wordpress" {

name = "technicloud-wordpress"

organization = tfe_organization.technicloud.id

}

# Add Web Dev Team

resource "tfe_team" "web-dev" {

name = "technicloud-web-dev"

organization = tfe_organization.technicloud.id

}

# Add User to Web Dev Team

resource "tfe_team_member" "user1" {

team_id = tfe_team.web-dev.id

username = "rfitzhugh"

}

resource "tfe_team_access" "test" {

access = "plan"

team_id = tfe_team.web-dev.id

workspace_id = tfe_workspace.technicloud-wordpress.id

}So basically…

You can find the above code sample on GitHub.

Summary

In this post I reviewed a handful of compelling Terraform Cloud features. This includes remote state management, cost estimation, and collaboration features. Consider using Terraform Cloud for state storage and collaboration (especially the Private Module Registry), it’s free for small teams (up to 5)! Since we do not yet use Sentinel, I did not get a chance to test out Sentinel policies with Terraform Cloud but hope to implement it soon.

If you have any questions, please reach out to me on Twitter.